|

My research falls broadly within the history and philosophy of psychiatry or, insofar as much of it precedes the emergence of that field, at the intersection of history of philosophy and history of mind and medicine. I am interested in the connections drawn between personhood and irrationality by British empiricist psychologists and philosophers of mind during the modern period, focusing especially on John Locke. I also work on contemporary epistemological and ethical issues surrounding the classification and diagnosis of disease, and have interests in applied medical ethics and experimental philosophy.

|

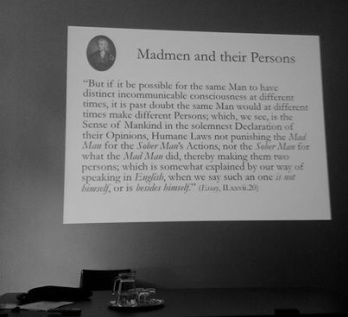

Early Modern PhilosophyMy book project, Agents and Patients: John Locke's Ethics of Thinking,

grew out of my doctoral work on Locke's theory of the association of ideas. There I argued that if Locke's treatment of associated ideas as a form of mental pathology is taken seriously, the received view that he is an appropriate figurehead for associationist psychology must be rejected. In my book, I show that Locke's interest in psychopathology extends farther than his theory of associated ideas. In his political tracts, Locke identifies the threat posed by zealotry and deviance to the stability of the civil state. In his theology, he speculates about how our mental hygiene impacts our moral accountability. And in his philosophy, he argues that, as early as infancy, the soundness of our ideas determines whether or not we are doomed to falsehood and delusion. Reading across his eclectic corpus, my book argues that Locke is first and foremost a physician of the mind, rather than a metaphysician, epistemologist, or even political philosopher. After presenting Locke’s medical account of the understanding, I use it to offer new interpretations of several of his doctrines that remain influential for contemporary philosophical and political thought: his theories of personal identity, of human freedom, of property rights, and of the justification of empire. |

|

This material also appears in some recent publications:

Other work in the history of early modern philosophy concerns related questions about theories of mind, rationality, and human nature in the seventeenth century:

|

Philosophy of Medicine and Medical Ethics

|

My interests in philosophy of medicine are mostly ethical and epistemological. My research focuses on psychiatry, specifically the role of classification in bridging the explanatory (research) and practical (clinical) aspects of that discipline.

Past work includes a critique of the role of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in psychiatric research, in which I argue that psychiatric progress has been stunted by the limitation of basic research to targets picked out by clinical tests. I explore the National Institute of Mental Health's RDoC project as an alternative approach to classifying psychiatric objects in my paper "Psychiatric Progress and the Assumption of Diagnostic Discrimination" (Philosophy of Science, 2015) and consider its implications for philosophers in "Philosophy of Psychiatry after Diagnostic Kinds" (Synthese, 2018). I have also worked with Kenneth F. Schaffner on issues surrounding social construction and explanation in psychiatry:

|

In a series of more recent papers, I explore the promises and perils of "precision psychiatry:

- Kathryn Tabb and Maël Lemoine, 2021. “The Prospects of Precision Psychiatry.” Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 42(5-6): 193-210.

- Kathryn Tabb, 2023. “Precision.” In Keywords for Health Humanities, ed. Sari Altschuler, Jonathan Metzl, and Priscilla Wald. MIT Press. Pp. 167-170.

- Kathryn Tabb, 2020. “Should Psychiatry be Precise? Reduction, Big Data, and Nosological Revision in Mental Health Research.” In Levels of Analysis in Psychopathology. Eds. Kenneth K. Kendler, Josef Parnas, and Peter Zachar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pages 308-334.

- *reissued as Kathryn Tabb, 2023. “La psychiatrie doit-elle être précise ? Réductionnisme, données massives et révision nosologique dans la recherche en santé mentale” in Paris: Hermann.

In 2016 I completed an MA in bioethics at the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Biothics and Health Law, which included two practica, one at UPMC's Shadyside Hospital (in the departments of medical ethics, oncology, and palliative care and in the ICU) and at re:solve Crisis Network. The abstract for my MA thesis can be found here.

Assessing Intuitions about the Genetics of Virtuous Behavior

Along with Paul Appelbaum (Psychiatry, Columbia University) and Matt Lebowitz (Center for Research on Ethical, Legal and Social Implications of Psychiatric, Neurologic and Behavioral Genetics, Columbia University) I am working on a three-year project investigating intuitions about genetics and moral responsibility as part of the Genetics and Human Agency initiative directed by Eric Turkheimer (UVA).

People tend to think that having a certain characteristic “in the blood” can affect how responsible we are for our actions. The genetic revolution has introduced new means for testing for the presence of such characteristics, which in turn has raised new puzzles about what it means to be “predisposed” toward certain actions. For example, if we could test for a genetic predisposition toward altruism, would the kind deeds of a person who tested positive become less admirable in our eyes? Or more? If a child is revealed to carry a gene associated with unusual levels of aggression and hostility, does it lead adults to punish her more for her bad behavior, or less?

One might assume that there is a general answer to such questions — that, for example, knowing someone to have a genetic predisposition toward acting in a certain way tends to make us feel that her behavior is outside of her control, and thus that she is less responsible for it (regardless of what the specific behavior may be). Or, alternatively, one might anticipate that because we see people’s genetic makeup as fundamental to who they really are, we judge people to be more responsible when they act in line with their genetic constitution. Our preliminary research, however, suggests that there is no uniform way we interpret genetic information in moral contexts. Instead, intuitions about the relevance of our genetic profiles to moral responsibility seem to vary with the sort of behavior in question — for example, we appear to see "bad" behavior as meriting less blame to the extent it is seen as genetically caused, but there is no corresponding decrease in the perceived praiseworthiness of "good" behavior when it is seen as rooted in DNA.

The aim of our project is to assess the diverse circumstances under which genetic attributions alter ascriptions of praise and blame. We are particularly interested in studying intuitions about the genetics of virtuous behavior, an area that has received less attention than intuitions about the role of genetics in criminality and other “vices” (and that seems to involve different psychological processes). Our hope is that our results will help people think more critically about how they integrate genetic information into their assessments of others, and ultimately, help inform our ethical conduct in the genetic age.

Publications from this project include:

One might assume that there is a general answer to such questions — that, for example, knowing someone to have a genetic predisposition toward acting in a certain way tends to make us feel that her behavior is outside of her control, and thus that she is less responsible for it (regardless of what the specific behavior may be). Or, alternatively, one might anticipate that because we see people’s genetic makeup as fundamental to who they really are, we judge people to be more responsible when they act in line with their genetic constitution. Our preliminary research, however, suggests that there is no uniform way we interpret genetic information in moral contexts. Instead, intuitions about the relevance of our genetic profiles to moral responsibility seem to vary with the sort of behavior in question — for example, we appear to see "bad" behavior as meriting less blame to the extent it is seen as genetically caused, but there is no corresponding decrease in the perceived praiseworthiness of "good" behavior when it is seen as rooted in DNA.

The aim of our project is to assess the diverse circumstances under which genetic attributions alter ascriptions of praise and blame. We are particularly interested in studying intuitions about the genetics of virtuous behavior, an area that has received less attention than intuitions about the role of genetics in criminality and other “vices” (and that seems to involve different psychological processes). Our hope is that our results will help people think more critically about how they integrate genetic information into their assessments of others, and ultimately, help inform our ethical conduct in the genetic age.

Publications from this project include:

- “Asymmetrical Genetic Attributions for the Presence and Absence of Health Problems.” Psychology & Health, 2022.

- Matthew S. Lebowitz, Kathryn Tabb & Paul S. Appelbaum, 2021. “Genetic Attributions and Perceptions of Naturalness are Shaped by Evaluative Valence.” The Journal of Social Psychology.

- Lebowitz, Matthew, Kathryn Tabb, and Paul Appelbaum, 2019. “Asymmetrical Genetic Attributions for Prosocial Versus Antisocial Behaviour.” Nature Human Behaviour, 3(9): 940-949.

- Kathryn Tabb, Matthew S. Lebowitz, and Paul Appelbaum, 2018. “Behavioral Genetics and Attributions of Moral Responsibility.” Behavior Genetics 49:128-135.

Darwin

My MPhil work at the University of Cambridge centered on Charles Darwin, specifically the role of teleology and of intentionality in his theory of natural selection. Enduring interests include Darwin's views on inbreeding, instinct, and insanity. In a current project I argue that Darwin's early interest in associationist theories of madness (recorded in his unpublished notebooks) draws upon the tradition I'm calling Lockean medical associationism, and demonstrates its enduring influence on medical psychology.

I also have a paper on Darwin's work on orchids in Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences -- Darwin at Orchis Bank: Selection after the Origin.

I also have a paper on Darwin's work on orchids in Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences -- Darwin at Orchis Bank: Selection after the Origin.

Book Reviews

Miscellaneous Collaborations “The Duplicity of Habit: On the Association of Ideas in the Scottish Enlightenment,” with John P. Wright (In Oxford History of Scottish Philosophy in the 18th Century, Vol. 2, 2023).

|